What is Perthes disease?

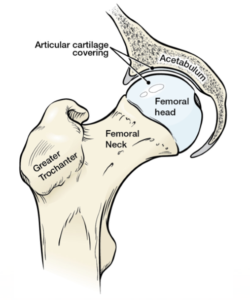

Perthes disease is a childhood hip disorder caused by a disruption of blood flow to the ball of the hip joint, or femoral head. The loss of blood flow results in bone death, which is referred to as “avascular necrosis” or “ischemic necrosis” of the femoral head. Perthes disease is also referred to as Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease or Legg-Perthes disease. The names come from the three men who first reported the disease in 1910 – Arthur Legg (USA), Jacques Calvé (France), and Georg Perthes (Germany).

What causes it?

We do not know what causes the disruption of blood flow. Perthes disease does not have a strong genetic inheritance, and in fact, only about 5 percent of the patients have a family member with the condition. It also does not appear to be caused by direct hip injury. Some studies have shown an association between Perthes disease and exposure to cigarette smoking, rare blood clotting disorders, hyperactivity and attention deficit disorder, and minor congenital abnormalities like inguinal hernias and undescended testes.

Who gets it?

Perthes disease affects a wide age range of children but the most common age range is between 4 and 9. Boys are four times more likely affected than girls. Ten percent of patients will have Perthes in both hips, referred to as bilateral disease. Usually one side is affected first and followed by the other side a few years later. There is some variation in the frequency of Perthes disease between different regions and ethnic groups.

What are the symptoms?

In general, Perthes disease produces symptoms that have a gradual onset. Pain and limping are two common symptoms. The limping is often worse with activity and often usually improves with rest. Pain is usually not specific to the hip. More often, children experience thigh or knee pain which delays proper diagnosis. Parents may notice that the movement of the affected hip is less than the unaffected side.

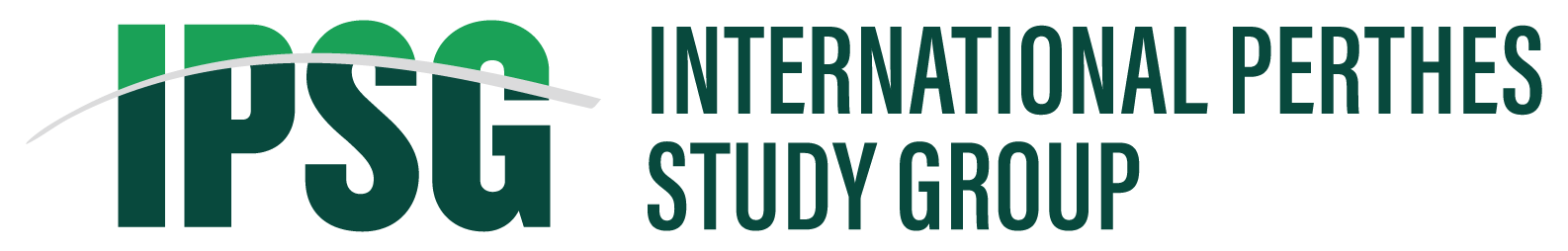

Stage 1: Initial or Avascular Necrosis Stage

On x-rays, the femoral head looks whiter and smaller than the unaffected side due to the disruption of blood flow that causes bone death. Early flattening of the top of the femoral head or fracture line (called subchondral fracture or crescent sign) can be seen. This stage generally is less than one year.

Stage 2: Fragmentation or Resorptive Stage

In this stage, the femoral head looks irregular and broken up (fragmented) with a more flattened appearance. These x-ray irregularities are due to the dead bone being removed by the healing process creating areas without bone (seen as dark areas on x-rays). The removal of the dead bone is called resorption and thus this stage is sometimes referred to as the resorptive stage. The femoral head can also appear to be moving out of the socket (called lateral subluxation or extrusion). This stage generally lasts 1 to 1 1/2 years.

Stage 3 Reossification Stage

In this stage, new bone (seen as increased white appearance of the femoral head) starts to fill in the areas where the dead bone has been removed. The newly-formed bone can be seen along the outer perimeter of the femoral head that gradually fills in towards the central area. Because the new bone is filling in, this stage is called the ossification stage. This stage is usually the longest stage and can take 2-3 years.

Stage 4: Healed Stage

In this stage, the appearance of the bone in the femoral head looks similar to the normal side. It is homogeneous and the irregular, fragmented appearance is no longer seen. The affected femoral head, however, can be enlarged (called coxa magna), flattened (coxa plana), and have a short, broad neck (coxa breva). The final shape of the femoral head at this stage (the degree of flattening or deformity) and how it fits the socket largely determines the long-term outcome. This is the stage where Stulberg radiographic classification is applied.

How is Perthes diagnosed?

The diagnosis requires a careful history, physical examination, and x-rays. In patients with Perthes, leg pain, decreased hip movement, and limping are seen. Since these symptoms and signs are not specific to the disease, x-rays are required to confirm Perthes.

Other childhood hip conditions can mimic Perthes disease. These must be excluded, such as transient synovitis, corticosteroid induced osteonecrosis, sickle cell disease, and multiple epiphyseal dysplasia.

In Perthes, x-rays will show changes to the appearance and the shape of the femoral head. Based on the changes, the stage of the disease can be determined. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using gadolinium contrast can assess the blood flow to the femoral head and provide more detailed information about how much of the femoral head is affected.

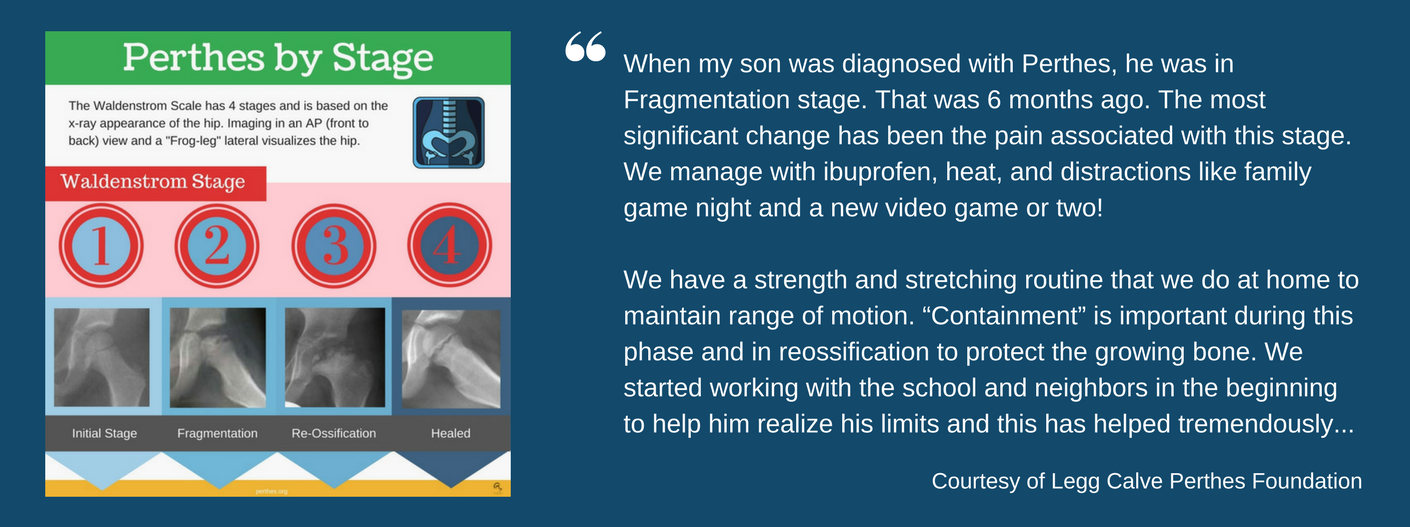

What is the prognosis?

It is best to divide the discussion into short-term, within 5 years, and long-term prognosis, 20-40 years later.

Short-term prognosis: Most of the patients will be able to return to full activities including sports with minimal symptoms once the femoral head has healed.

Long-term prognosis: This depends on the shape of the femoral head and how well it fits the socket at the time of skeletal maturity. This is approximately age 14 for girls and age 16 for boys. If the femoral head is very flat or irregular and does not fit the socket well, there is a high chance of getting degenerative arthritis and need for a hip replacement as an adult, even as early as the thirties and forties. Children who are older at the onset of Perthes and those who have the femoral head move out of the socket are more likely to require a hip replacement.

What factors affect the prognosis?

Shape of the femoral head, age at onset of disease, and the amount of disease involvement affect outcome defined as developing degenerative arthritis of the hip joint. Children under 6 tend to have a better outcome with less lasting deformity and a shorter duration of disease. Patients over 8 years tend to have a worse outcome.

Outcomes of Perthes patients who had a hip replacement:

For patients with Perthes who ultimately require a hip replacement as an adult, the outcomes are quite good. In one report, over 95% of hip replacements were doing well at 15 years after surgery, with a marked improvement in function. Unfortunately, the complication rate of surgery was higher than the typical hip replacement, particularly with regard to sciatic nerve injuries. In another study, patients with Perthes and an abnormal socket had a more than two and a half times the risk of postoperative hip dislocation in the first six months after surgery. Long-term outcomes in this study however, revealed that patients with Perthes did as well as others having a hip replacement.

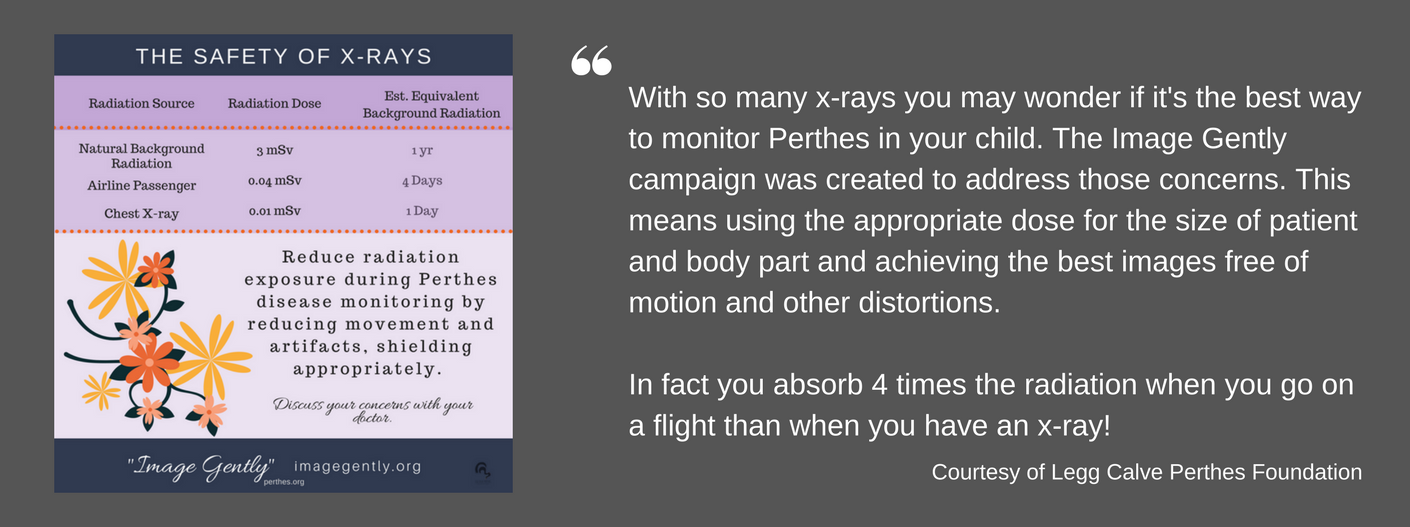

X -Ray Imaging

X-rays are a mainstay of diagnosis and management of Perthes. First, x-rays help physicians determine how far along the disease has progressed. Second, x-rays also provide information about the amount of hip deformity over the course of the disease and can show if the femoral head is developing signs associated with a poor outcome.

X-rays are usually obtained every 3-4 months during the active stage of Perthes to see if the disease is getting worse or better. X-rays of the hip can appear normal if symptoms arise during the very early stage of Perthes and if they have a short duration of only 1-2 months. In these cases, MRI may be required to make the diagnosis.

Bone Scan

Bone scans, or scintigraphy, use radioactive material that collects in the areas of blood flow and increased bone remodeling or regrowth. Thus, the bone scan shows no radioactive material collection in the early stage of Perthes when there is no blood flow to the femoral head which is a sensitive way to see that the blood flow to the femoral head has been affected. The radioactive uptake increases as blood flow returns and the bone starts to heal. A bone scan is used less frequently now since a contrast MRI can provide more information without the need to use the radioactive material.

MRI with Gadolinium

Regular MRI without contrast provides detailed anatomical information about the affected hip joint in Perthes including hip joint inflammation, amount of deformity, and which part of the femoral head is affected. In the early stage of Perthes, however, a few cases of false-negative findings have been reported when no contrast was used. In these cases, the hip appears normal despite the presence of Perthes disease.

MRI with gadolinium, or contrast-enhanced, generates detailed pictures of blood flow in the femoral head allowing physicians to quickly tell how much of the femoral head is affected with Perthes. In order to visualize the blood flow, contrast is administered intravenously into the body and images are collected over time to visualize how the contrast flows into the femoral head. Since these duration of time required to collect these images is longer than most children younger than 8 are able to usually tolerate while remaining still, some sedation is often used.

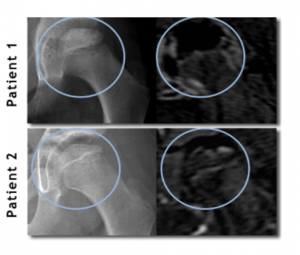

MRI with gadolinium, also called perfusion MRI, is very sensitive imaging tool that provides blood flow status of the hip. It is able to detect the lack of blood flow in the femoral head before any x-ray changes occur. As contrast MRI can show how much of the femoral head is affected by Perthes, it may also help predict who will do well without surgical treatment and who will do better with surgical treatment. One of the goals of IPSG is to assess how well MRI with gadolinium can predict these outcomes. This image compares how an MRI with contrast can show more detailed information than an x-ray alone. The x-ray images on the left from two different patients appear relatively similar, however the MRI images on the right show that patient 1 has much greater femoral head involvement than patient 2 does. In the MRI images, areas that appear gray show where blood flow is carrying contrast to the hip. Since Perthes is characterized by a loss of blood flow to the femoral head, the areas of the hip affected by Perthes receive no contrast and appear black on the MRI with contrast images.

Arthrogram

Hip arthrography is generally performed in the operating room. A dye is injected into the hip joint space and x-rays are taken with the affect leg in different positions to assess the shape of the femoral head and how well it is fitting into the socket or acetabulum. It is usually performed before putting on Petrie casts and/or performing hip adductor surgery.

Helpful Links

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons was founded in 1933 to provide educational services for orthopaedic surgeons and engages in advocacy activities on behalf of patients and the orthopaedic profession.

Legg Calve Perthes Foundation

LCPF’s focus is on the whole family and their mission is to create a centralized support community to improve the research, education, and awareness of those diagnosed with Perthes. Join the Patient Contact Registry at Perthes.org to further Perthes research.

Perthes on Facebook

Social media is helping families worldwide to connect and deal with Perthes. Here are several Perthes disease groups and pages where you can participate in discussions and connect with others along the same journey. Remember that Perthes disease is a complex disease; it’s important to discuss health decisions with a qualified orthopaedic surgeon.

Perthes Kids Foundation

Perthes Kids Foundation was established by Earl Cole who was diagnosed with Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease as a child and founded this charity to help raise awareness, funds, further research, find a cure, and connect others dealing with this rare hip bone disease. Every year all over the world, Camp Perthes gives kids with Perthes a chance to play and connect with others.